Choanoflagellates and the Origins of Animal Life on Earth

How a single-celled eukaryote led to the evolution of intelligent multicellular life.

Where do animals come from?

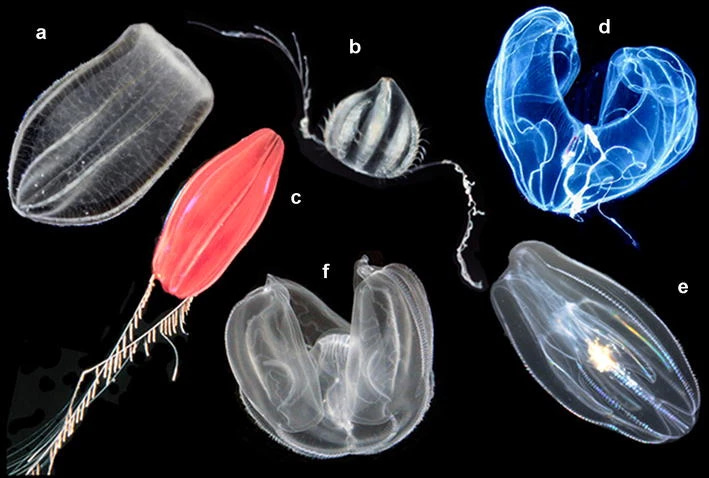

The beginning of animal life has puzzled evolutionary biologists for centuries, sparking many debates over which group of organisms first diverged in the tree of life. The mystery deepens as new genetic studies continue to challenge traditional views. At the heart of this debate are two primary contenders: the sea sponges (Porifera) and the comb jellies (Ctenophora). Interestingly enough, the key to understanding this evolutionary puzzle lies in a strange, little microorganism that most people live their lives without ever knowing exists.

What are choanoflagellates?

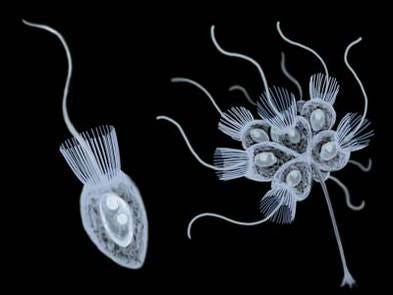

Choanoflagellates or “collar-flagellates” are a fairly simple group of free-living, single-celled protists that can be found in both fresh water and marine environments. They derive their name from a ring of closely packed microvilli, thin projections that surround the single flagellum like a collar by which choanoflagellates take in food and use for locomotion.

They feed by beating their flagella to draw water through the microvilli collar, filtering out bacteria and small food particulate. In the case of free-living choanoflagellates, they also use the flagellum to move forward in the water, however, many species can remain attached to a substrate by a long, thin stalk. Unfortunately, not much is known about the life cycle and history of choanoflagellates since they remain a cryptic and unconventional subject of study.

Although choanoflagellates have no comprehensive fossil record, evolutionary biologists can infer their existence to at least the Late Precambrian, due to their remarkable affinity with one of the most primitive animals, or metazoans, alive today.

Porifera-First Model

Sea sponges all belong to the metazoan phylum Porifera and are extremely variable in size, shape, colour, and ecology. They are widely regarded as the earliest and most primitive group of animals to have branched off from the evolutionary tree of life, though recent genetic studies and debates pit them against the comb jellies as the oldest group of animals.

Sponges have a very peculiar and unique biology. While generally considered a single animal, the individual cells of sea sponges are so specialised in engineering a variety of bodily functions that they appear to be more independent of each other than the cells of other animals. Their nervous and digestive systems are more akin to those of an animal colony than a singular organism.

The relationship between choanoflagellates and our early animals, the Porifera, comes from the way sponges feed. Choanoflagellates are nearly identical in shape and function to choanocytes, or collar cells, in sponges. These cells beat their flagella in the same way choanoflagellates do so that a unidirectional current draws water and food particles through the body and pores of a sponge, continuing to filter out food particles with their microvilli. Sound familiar?

Other Models and Additional Complications

The Ctenophora-First model proposes that comb jellies, not sponges, represent the earliest branching lineage of animals. This theory emerged as a response to genomic analyses suggesting that ctenophores, with their more complex nervous systems and tissues, might have diverged before the simpler sponges. This goes to challenge the long-held assumption in evolution that simplicity in form and function implies an earlier origin; raising intriguing questions about the evolution of metazoan complexity. If ctenophores had truly evolved first, this would imply that key animal traits like neurons and muscles either evolved multiple times independently or were lost in other lineages like Porifera.

Both the Porifera-First and Ctenophora-First models come with their own set of complications. The Porifera-First model, while aligning with the idea that simpler organisms came first, faces genetic evidence suggesting otherwise. Meanwhile, the Ctenophora-First model, although supported by molecular data, presents the paradox of why sponges, the simpler organisms, appear to have a more primitive body plan if they evolved later. Even more so, ctenophores’ highly specialised nervous system and musculature makes it difficult to explain how they could precede the simpler colony-like structure of sponges.

The long-winded debate over the origins of animal life is far from settled. Both the Porifera-First and Ctenophora-First models offer compelling yet conflicting perspectives on early animal evolution. So long as new genomic tools and methods evolve, scientists will continue to hope to refine these models and uncover more definitive answers. For now, the origin of animals remains a mystery deeply intertwined with the life history of our early metazoan and their weird and wonderful single-celled cousins as we continue to explore the fascinating early branches of the tree of life.

Well written Ms Cordes!